Marked for Deportation - Why Finding Gang Members by Tattoos is Quick, Easy, and Wrong

World of Crime traces back the history of tattoos being used to profile suspected gang members from MS-13 all the way to Tren de Aragua

Gang members have tattoos. But so do plenty of other people. If recent reporting on the deportation of over 200 Venezuelan migrants to El Salvador is to be believed, US law enforcement has become dangerously reliant on tattoos as the sole means to identify someone as a gang member.

Documents from the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Justice, and police departments across the United States, reviewed by World of Crime and other media, show how using tattoos to justify describing suspects as gang members has become common practice.

In this report, World of Crime breaks down how tattoo profiling began in the US and why it doesn’t work.

Origins of Tattoo Profiling in the US

Tattoo identification has deep roots in US policing, especially in efforts to combat gangs composed largely of Latin American immigrants or their descendants. In the 1980s and 1990s, law enforcement began documenting tattoos as visual evidence of gang affiliation. Central American street gangs like Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) became notorious for their heavy use of tattoos to proclaim loyalty.

Police gang units were trained to recognize common symbols – for example, MS-13 members often tattooed “MS” on their bodies – reinforcing the perception that certain tattoos equate to gang membership.

This era saw the rise of gang databases and manuals instructing officers in tattoo and symbol recognition. The FBI even established a dedicated Tattoo and Graffiti ITAG) team to catalog thousands of tattoo images and assist in investigations.

During the 1990s, the practice of photographing and cataloguing gang tattoos spread from big-city police departments to federal agencies. Immigration authorities also took note. By the early 2000s, as US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) launched programs targeting “transnational street gangs,” tattoos were explicitly used as criteria to identify suspects.

Law enforcement training materials from this period often included extensive lists of tattoo patterns and their supposed meanings – from common icons (like crowns or stars) to letters and numbers signifying gang initials or area codes.

A 2008 report on tattoos by the Canada Border Services Agency ran to 84 pages, with such simplistic descriptions as “skulls generally designate murderers.”

However, even in this early phase, there were warnings that tattoos alone could be misleading. Some police training manuals cautioned that tattoos with neutral or cultural significance (like religious imagery) are “not necessarily” evidence of gang affiliation, acknowledging the risk of false positives. Despite those caveats, a growing ethos of zero tolerance meant many officers treated any unfamiliar tattoo on a Latino immigrant as a potential gang sign.

Expansion into Immigration Enforcement

By the 2010s, tattoo profiling had firmly entered US immigration enforcement. ICE agents, Border Patrol officers, and local police working with federal task forces increasingly relied on tattoos when deciding if a migrant was in a gang. This trend accelerated under hardline policies. In 2017, the Trump administration prioritized deporting Central American gang members and “took the handcuffs off” officers to use all tools available

Tattoos became a shortcut for suspicion – sometimes with flimsy evidence. A high-profile example was the case of Daniel Ramirez Medina, a young DACA recipient swept up by ICE near Seattle in 2017.

Ramirez, a 23-year-old with no criminal record, was living in Washington State when ICE agents arrested him during a raid, allegedly because they believed he was a gang member. Their suspicion rested largely on a tattoo on Ramirez’s forearm. The tattoo read “La Paz BCS”, which refers to La Paz, Baja California Sur – Ramirez’s birthplace – and also means “peace” in Spanish. ICE, however, misinterpreted this tattoo as a gang indicator. Agents claimed the tattoo, combined with Ramirez’s admission that he had once “hung out” with some people in California, signified affiliation with the Sureños (southern California gang network) or a local clique (which ICE called “Paizas”).

Ramirez denied any gang membership, but ICE moved to revoke his DACA status on the basis of alleged gang ties, citing him as a public safety risk. This case became a cause célèbre because Ramirez was one of the first DACA enrollees detained under the new immigration enforcement policies. His lawyers accused ICE of flawed tattoo profiling – essentially, seeing a common phrase and locale (“La Paz”) as a gang moniker. After being held in detention for 47 days, Ramirez was ordered released by an immigration judge on March 29, 2017. Subsequent legal battles led to a settlement in 2023 in which the US government cleared Ramirez’s record of any gang allegations and granted him a temporary stay of removal

Immigration advocates noted this was not an isolated incident – around the same time, at least nine immigrant teenagers in Long Island were detained based on unconfirmed gang allegations, including doodles and fashion choices misidentified as gang signals

One 19-year-old asylum seeker from Honduras was arrested after his high school reported the devil horns mascot he sketched in class; authorities misconstrued it as an MS-13 symbol.

Civil liberties groups and researchers grew alarmed at these patterns.

A 2018 report by the New York Immigration Coalition and CUNY School of Law found that officers were “relying too much” on superficial indicators – clothing, hand gestures, and tattoos – as grounds for gang affiliation

“The emphasis on physical appearance dangerously results in stereotyping Latinx communities and inherently encourages race-based policing,” the report warned.

In practice, being a young Latino male with a tattoo could trigger a gang accusation in the eyes of some officers. This period also saw local law enforcement sharing information with ICE: school police or town gang units would flag migrant youth for “gang tattoos” or styles, leading to immigration detention without substantive proof of criminal activity

Such collaborations landed dozens of New York-area teenagers in ICE custody—some for nothing more than a Chicago Bulls T-shirt or a rosary tattoo that authorities deemed suspicious. These early controversies exposed how tattoo profiling, once reserved for known gang members, had broadened into a blunt instrument casting a wide net over immigrant communities. Critics argued that law enforcement was conflating cultural expression with criminality, often violating due process in the rush to deport alleged gang members.

MS-13 and Barrio 18 Tattoo Practices and US Response

MS-13 and Barrio 18, the two most prominent transnational gangs from Central America, embraced tattooing in their culture from early on. In the 1980s and 1990s, many members proudly displayed large, extravagant tattoos as a visible badge of identity

In El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala – as well as among clique members in US cities – it was common to see gang affiliates with head-to-toe ink. Photographs from prisons in the 2000s show inmates completely covered in gang tattoos, which “glorify the Los Angeles gang life” that birthed these groups

An MS-13 veteran might have “MS” or Salvatrucha emblazoned across his back or chest, devil horn symbols on his arms, and maybe even facial tattoos of tear drops or the number 13. Barrio 18 members likewise tattooed “18”, “XV3”, “Dieciocho” (Spanish for 18), or the word Bestia (beast, a code for 18 as 6+6+6) on their bodies. These markings served not only as intimidation and pride, but also as a form of resume within the gang – a heavily tattooed member was often one who had proven his commitment. As one gang member in El Salvador lamented during a crackdown, “just because we have tattoos, we get arrested… whether we committed a crime or not” – a statement that illustrates how indelible these tattoos were in marking someone for life, in the eyes of society and law enforcement alike. Ollder gang members often found their tattoos to be a barrier to leaving the gang; even if they wanted out, the markings on their skin made it hard to avoid being identified (or targeted by rival gangs).

Crackdowns and Evolution: The turn of the millennium brought aggressive anti-gang campaigns in Central America – notably El Salvador and Honduras. Simply appearing to be a gang member (for example, sporting tattoos or wearing gang colors) was enough to warrant arrest.

Police in San Salvador and Tegucigalpa began sweeping up youths with tattoos, throwing them in overcrowded prisons on suspicion alone. As one Mara Salvatrucha member in El Salvador described, authorities would “grab the first three or four young people… and [call] them suspects… They blame gang members for every single crime”. And tattoos made an easy target.

Tattoos went from being a source of pride to a liability – a literal bull’s-eye that drew police attention. Gang members began tattooing only in covered areas (torso, legs, back) or avoided new tattoos altogether to better blend in. The once-common full-face tattoos became rare among the newer generation.

US Law Enforcement Response: As MS-13 and Barrio 18 expanded their presence in the United States (often via immigrants fleeing war or deportees sent back from the US American law enforcement ramped up efforts to identify and track gang members – and tattoos were a key part of that strategy. Starting in the mid-2000s, federal agencies launched initiatives like Operation Community Shield (ICE’s anti-gang crackdown begun in 2005) to arrest and deport transnational gang members. A major challenge was identifying who was in a gang, especially if they hadn’t been convicted of crimes yet. Here, tattoos and graffiti intelligence became invaluable. Police had long used photographs of scars and tattoos to help ID suspects, but now agencies began systematizing it.

They compiled databases of tattoo images and gang lore. The Department of Homeland Security (which includes ICE and Border Patrol) worked with countries like El Salvador to exchange information on gang tattoos, so that an arriving migrant with certain markings could be flagged. In 2014, the FBI integrated tattoo recognition into its Next Generation Identification system, enabling officers to query a tattoo description or image and find potential matches in criminal records.

US officials also disseminated informational materials: for example, an FBI National Gang Intelligence Center report would include photos of MS-13 hand signs and tattoos to educate local police. Agencies like ICE and CBP developed comprehensive gang questionnaires and screening tools, which included documenting any tattoos on new detainees. In some cases, suspected gang members were asked to remove shirts so officers could photograph their tattoos for analysis. The FBI’s TAG team (discussed earlier) played a role in supporting these efforts by offering its analytical expertise to any agency that found an unfamiliar symbol.

Mano Dura: Since March 2022, El Salvador has undergone one of the most sweeping anti-gang crackdowns in modern Latin American history — and tattoos have become a primary basis for arrest. Under President Nayib Bukele’s “war on gangs,” the Salvadoran government has suspended constitutional rights, authorized mass detentions, and criminalized appearance-based suspicion, casting tens of thousands into prison. The result is a security policy praised for lowering homicide rates, but widely condemned for trampling due process, especially for those marked by body ink.

The campaign began following a spike in homicides in late March 2022, when 92 people were killed in a single weekend — an eruption of gang violence attributed to a breakdown in secret negotiations between Bukele’s government and gang leaders. In response, Bukele declared a “state of emergency” that suspended basic civil liberties: freedom of assembly, communication privacy, and key legal protections like the right to be charged within 72 hours.

Over the next two years, more than 85,000 people were arrested — a staggering figure for a country of just 6.3 million. Among the primary tools used by security forces to identify alleged gang members: tattoos. Law enforcement began systematically targeting individuals with visible tattoos during street patrols and raids. In many neighborhoods, soldiers ordered men to lift their shirts so their torsos, arms, and backs could be inspected for ink. Those with tattoos deemed gang-related — or sometimes just “suspicious” — were detained on the spot.

The logic draws on the country’s history. As aforementioned, El Salvador’s dominant gangs — MS-13 and Barrio 18 — have used tattoos to signal affiliation, rank, and identity. Members often bore dramatic ink: faces, hands, necks, and full torsos branded with gang numbers, letters, or symbolic icons like spiderwebs, teardrops, or weapons. But by the mid-2000s, amid regional crackdowns, many gang members began hiding or avoiding tattoos altogether, knowing they had become a liability. Today, tattoo visibility is no longer a reliable indicator of gang membership — yet Salvadoran authorities continue to treat them as such.

Under the state of emergency, police made no distinction between active gang members and those who had left gangs — or people who were never involved at all. Having a tattoo, particularly in a marginalized neighborhood, became grounds for imprisonment. Rights groups and local journalists documented case after case where men were arrested for innocuous tattoos: a praying hands tattoo for a grandmother, a crown with the word “God,” even a biblical verse. Former gang members who had gone through rehabilitation programs and left crime behind were also swept up — their tattoos a permanent mark of suspicion.

International human rights organizations have raised the alarm. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have both accused El Salvador of systematic due process violations. Their investigations revealed mass arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, torture in detention, and dozens of deaths in custody. Many prisoners are held without formal charges, trial dates, or access to lawyers. Family members often go weeks or months without learning where their loved ones are held — or whether they’re alive.

Bukele, meanwhile, remains unapologetic. His administration touts the crackdown as a success: murders have plummeted, extortion rings have weakened, and once-feared gang territories are now under military control. His approval ratings remain sky-high domestically. When asked about the potential for wrongful arrests, Bukele acknowledged that “1%” might be innocent — but added that it was a necessary sacrifice. Critics, however, argue that 1% of 85,000 is still 850 innocent people in prison. In fact, the number is likely far higher.

The Tren de Aragua Crackdown

In late 2024 and early 2025, tattoo-based profiling leapt back into national headlines with a controversial US crackdown on Venezuelan migrants accused of belonging to Tren de Aragua – a Venezuelan crime syndicate. In February 2025, US authorities designated Tren de Aragua as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, and soon after, President Donald Trump invoked the Alien Enemies Act (a 1798 wartime law) to summarily deport hundreds of Venezuelan asylum-seekers deemed security threats.

In March 2025, over 200 Venezuelan men were abruptly shipped out of the country on flights to a mega-prison in El Salvador. They were alleged to belong to Venezuelan gang, Tren de Aragua, and were jailed in Bukele’s new super-prison, alongside Salvadoran gang members and many others.

Many had no criminal history whatsoever, according to their lawyers who spoke to The Guardian, they were swept up largely because of tattoos and tenuous associations. An official Department of Homeland Security memo reviewed by reporters stated outright that one detainee, 26-year-old Franco José Caraballo, “has been identified as a member…of Tren de Aragua,” while in the same breath admitting he had “no known criminal history” and citing only that he had several tattoos.

.

Caraballo’s lawyer blasted the accusation: “It’s specious – there’s no basis for this conclusion,” he said, noting that experts in Venezuela have all stated there are no tattoos that associate [Tren de Aragua] gang members.

Unlike MS-13, the Tren de Aragua does not use tattoos as an organizational marker, and many actual members have no tattoos at all, according to Venezuela gang researchers and extensive research by World of Crime.

Despite this, US agents appeared to lean on body art as proof of guilt. Caraballo, for example, sported a rose, a lion, a barber’s razor blade (denoting his trade), a pocket watch with his daughter’s birth time, and his daughter’s name on his chest.

Nothing obviously nefarious – yet during his detention interview in Dallas, officers pointed to those tattoos as evidence he belonged to Venezuela’s most notorious gang.

He was deported to El Salvador in shackles. His case is one of many.

“He’s just a normal kid…he likes tattoos – that’s it,” Caraballo’s attorney told The Guardian, arguing that immigration agents effectively criminalized a common form of personal expression.

Family members of other deportees tell similar stories. Jhon Chacín Gómez, a Venezuelan in his thirties and now in the Salvadoran prison, had no criminal record; “ICE agents told him he belonged to a criminal gang because he had a lot of tattoos,” his sister recounted.

Another deportee, Edwuar Hernández, has four tattoos — his mother’s and daughter’s names, an owl, and ears of corn — “These tattoos do not make him a criminal,” his mother pleaded, insisting he was never in a gang.

In case after case, the only “evidence” seems to have been was ink on skin. US authorities have provided little public proof beyond that to justify the mass gang designations.

In a federal court filing, a senior ICE official even conceded that “many” of the expelled men had no criminal records – unsurprising, he admitted, because most had only recently arrived in the US as asylum-seekers.

In other words, many of these individuals had only their nationality and tattoos to tie them to alleged gang activity.The most high-profile example is perhaps Jerce Egbunik Reyes Barrios, a 36-year-old former professional soccer player. Reyes had fled Venezuela after reportedly being tortured for protesting against the Maduro regime, and was seeking asylum in the US.

Nonetheless, he was detained and marked as a Tren de Aragua operative – largely, it appears, because of a single chest tattoo. The tattoo depicts a crown atop a soccer ball with the word “Dios”. To an untrained eye, it looks like the logo of Real Madrid, Reyes’s favorite football club.

But to ICE agents scanning for gang signs, a crown and ball were enough to sound alarms. A DHS spokeswoman, Tricia McLaughlin, later cited Reyes’s tattoo as “consistent with those indicating TdA gang membership.”

On social media, she asserted that intelligence went beyond a single tattoo, but in the same post she doubled down that “he has tattoos” suggesting gang ties. Reyes’s attorney Linette Tobin refuted this vigorously, explaining that the design was a sports tribute, not a criminal emblem.

Other deportees were tagged based on similarly ordinary tattoos. One man was accused due to an eyeball tattoo – he told officials he’d simply found the design online because it “looked cool,” not knowing it would later be deemed a gang mark. Another, Gustavo Aguilera, a Dallas roofer and father of a US citizen child, was labeled a gang member because of three tattoos: a crown with his son’s name, a star with his own and his mother’s name, and the phrase “Real Hasta La Muerte” on his arm.

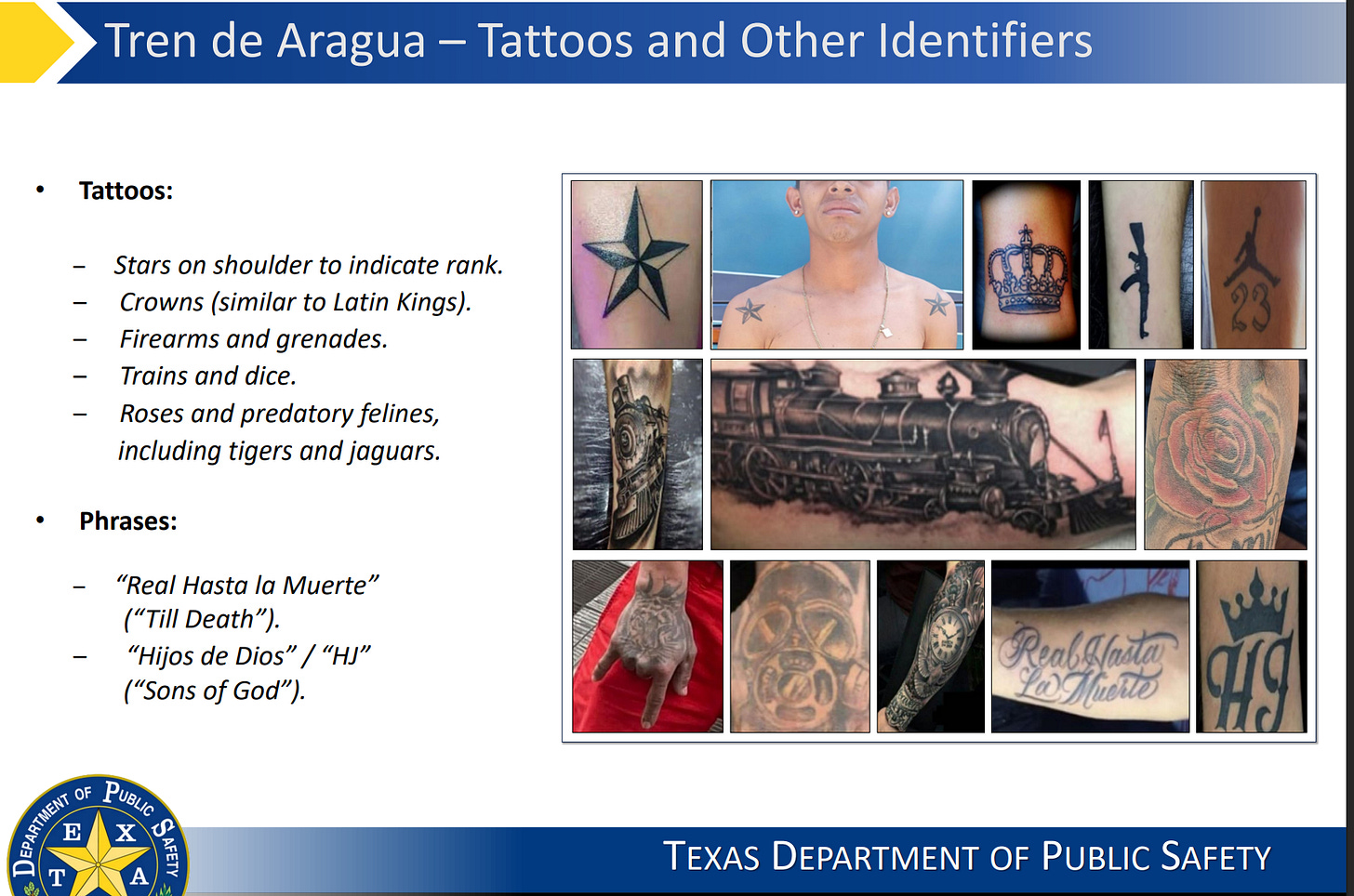

Ironically, “Real Hasta La Muerte” (Spanish for “Real Until Death”) is the motto of popular Puerto Rican reggaeton artist, Anuel AA, not a Tren de Aragua slogan. But in September 2024, the Texas Department of Public Safety circulated a report listing crowns, stars, roses, predatory felines, and that very phrase “Hasta la Muerte” as telltale Tren de Aragua tattoos.

This “profile” of gang tattoos, now proven to cast a wide net, seems to have primed federal agents to view virtually any Venezuelan migrant’s body art with suspicion. Lawyers point out that many of the motifs Texas flagged – e.g. crowns or stars – are extremely common tattoo choices with no gang meaning in Venezuela.

“Often they mean nothing at all,” public defender Karla Ostolaza, who has defended immigrants targeted for tattoos as trivial as a Jordan basketball logo, told the AP. A tattoo that would “set off no alarm bells in a suburban US gym” can, when worn by a Latino immigrant, “become a sign of criminality” in the eyes of authorities, she observed.

The result of this dragnet: dozens of men with family tributes, religious imagery, or artistic designs inked on their bodies have been condemned as hardened gangsters. Venezuela’s Tren de Aragua, which started in a prison but expanded into a crime network, is indeed a dangerous group – but experts stress it has no fixed tattoo iconography.

“Tren de Aragua has no identifying tattoo…some members are tattooed, others not,” said Ronna Rísquez, a Venezuelan journalist who wrote a book on the gang.

She and other analysts flatly reject the idea that tattoos are a meaningful indicator of Tren de Aragua membership.

Government Justifications and Legal Concerns

Homeland Security and immigration authorities have defended their actions in public, but their explanations reveal an uncomfortable reliance on thin evidence. The Department of Homeland Security insists it did not rely on “tattoos alone” to identify gang members.

In a court filing, ICE official Robert Cerna claimed the agency’s identification of the Venezuelan men “did not simply rely on…tattoos alone” and included social media and other intelligence. Likewise, DHS spokeswoman Tricia McLaughlin asserted that “intelligence assessments go beyond a single tattoo” and that officials are “confident” in their determinations

President Trump, for his part, portrayed the deportees as “bad people” and “thugs…from the prisons of Venezuela”, claiming a “very strong vetting process” was ensuring only real gang members were targeted. “We don’t want to make that kind of mistake,” Trump said regarding any misidentification, implying that if errors occurred, they would be corrected

US officials also pointed to social media posts or associations as corroborating evidence in some cases (for example, an online photo where one migrant made a hand gesture interpreted as a gang sign).

These justifications hinge on the idea that tattoos were just one factor among many.

However, immigration lawyers and human rights observers argue that, in practice, tattoos became the primary or sole basis for the gang label in most of these cases. “Tattoos were repeatedly used to argue that the men belonged to Tren de Aragua,” notes the Associated Press, summarizing multiple defense attorneys’ accounts

The speed of the removals also meant the usual standards of proof were largely absent – the men were expelled without hearings or chance to meet attorneys, under the extraordinary invocation of the 1798 Alien Enemies Act against Tren de Aragua.

That law allowed the government to bypass immigration courts entirely. Legal experts have called this a grave due process violation. “The United States now has a tropical gulag,” one analyst remarked, referring to the El Salvador prison deal.

In one court hearing, ACLU attorney Lee Gelernt revealed that multiple errors had occurred during the deportations – including at least one person sent to El Salvador who “was not even Venezuelan” and some women who were mistakenly shipped out before El Salvador refused to accept female prisoners

These mistakes underscore how hasty and sweeping the operation was.

Immigration attorneys argue that the government’s own statements betray its overreach. McLaughlin’s social media post, while insisting on multifaceted vetting, opened by citing tattoos as evidence

“It’s unjust to criminalize someone because of a tattoo,” Roslyany Camano, the wife of a deportee, told the LA Times, noting that by that logic she herself (with a rose tattoo) might be arrested and separated from her children.

Experts and former officials have criticized the strategy on pragmatic grounds as well. Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, a senior policy analyst at the American Immigration Council, told The Bulwark that using tattoos as a litmus test is extremely unreliable in this context. “Tren de Aragua is not a gang like MS-13 that mandates members get tattoos,” he explained. “Many tattoos associated with Tren are also very normal for a person to get, and that’s important to highlight because it increases the chances of getting this wrong.”

Conclusion

The use of tattoos as a proxy for criminality in US law enforcement doesn’t work. What may have begun decades ago as one element of gang identification has morphed into something wholly indiscriminate. Especially in the immigration context, tattoo profiling has often swept up individuals who have little to do with organized crime, conflating cultural expression with violent conspiracy. The recent saga involving Venezuelan asylum-seekers and Tren de Aragua allegations is a vivid case study.

It highlights how, under pressure to look tough on gangs, authorities leaned on an old heuristic – tattoos – to cast a wide net, at the expense of accuracy and justice. Legal safeguards were bypassed, and lives put at risk, largely over body art that in another context would be seen as benign or even banal.

In the US, the controversy is prompting some soul-searching. Courts and the public are asking whether targeting migrants “because of their tattoos” is compatible with American values and the rule of law.

The Department of Homeland Security faces tough questions on how it trains officers to distinguish true gang members from tattoo-loving youth – or whether such distinctions were even made in the rush to deport. The need for nuanced, evidence-based approaches is clear. A tattoo can be a clue, but it is not a crime.

Want to learn some interesting tattoo history? My podcast here explains it:

https://open.substack.com/pub/soberchristiangentlemanpodcast/p/the-hidden-history-of-tattoos?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=31s3eo

Excellent article! Well argued and good examples. It's bewildering how easy such symbols may become entangled with ideas about who is a criminal.