Liquid Cocaine and Liquid Meth - The New Winning Strategy for Drug Traffickers

Chemically concealed cocaine has been detected worldwide, but the true scale of the problem remains unverified. Two recent seizures of meth-infused clothing show the technique is spreading.

Every month, I review news about dozens of drug seizures and arrests. Most follow familiar patterns.

But a small detail buried in a recent statement by the Spanish police really caught my attention.

In mid-November, authorities in Catalonia arrested 14 people connected to Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel on suspicion of kidnapping and murder. The network was largely made up of Mexicans thought to have recently killed a drug trafficking contact from Kosovo.

Beyond the violence, what stood out was the group's method: receiving methamphetamine shipments from Mexico chemically infused into clothing.

This was not an isolated case. Earlier, on November 2, a British student was caught at Los Angeles International Airport carrying 13 T-shirts soaked in methamphetamine, destined for Australia. The meth, initially in powder form, had been dissolved with a solvent and blended into the fabric.

These were the first seizures I’d heard of chemically concealed methamphetamine. But this innovation shouldn’t be surprising—drug traffickers have been perfecting chemically concealed cocaine, also known as liquid cocaine, for years.

Why are liquid drugs such a threat?

Drug cartels have increasingly converted cocaine into liquid form, blending it into clothing, cardboard, paints, charcoal, and even sugar. While the technique isn’t new, advancements in chemical processes now mean far less cocaine is lost during production and extraction, making it a preferred smuggling method.

In March, the port of Rotterdam’s chief of police, Jan Janse, told me that:

“it’s about a new way of smuggling. They’re washing cocaine into textiles or cardboard or other types of goods. They then have to remove the cocaine from the goods so they need labs for that.

Washing cocaine into clothing or cardboard causes a lot of difficulties. It’s more complicated for drug traffickers than the rip-on/rip-off method but there’s very little chance of detection. Container scanners can’t pick it up.”

The EU Drugs Agency has also been warning about this trend. “It is likely that the large-scale processing of cocaine hydrochloride from imported intermediary products continues to take place in the European Union.

Their European Drug Report 2024 highlighted the scale of the issue:

In 2022, French authorities detected chemically concealed cocaine in 22 tonnes of sugar.

The same year, 100 kilograms of chemically infused coal was seized in Croatia.

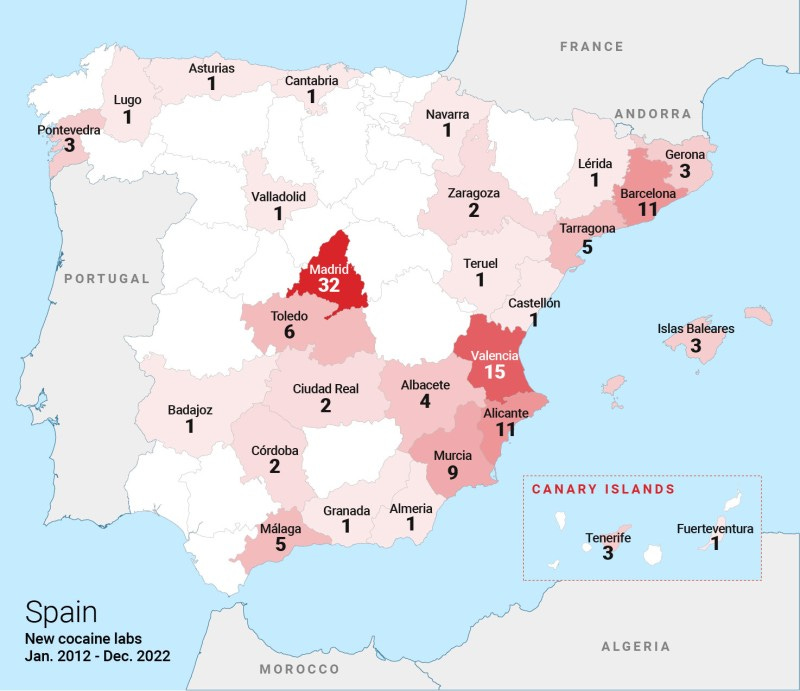

In Spain, a dismantled cocaine processing lab had the capacity to extract 200 kilograms daily from chemically concealed materials.

39 drug processing labs, used to extract the cocaine, were found in Europe in 2023.

This sophistication is expanding to methamphetamine, posing an even greater challenge.

So what’s being done about this?

Major entry points like Rotterdam are investing in solutions, but progress is slow. According to Janse, confirming the presence of liquid cocaine in seized materials can take up to two weeks. By then, any actionable intelligence is often stale. Rotterdam is now building a mobile detection lab to reduce delays.

However, these methods remain reactive. Liquid cocaine cannot be detected by X-ray scanners and most often, not by sniffer dogs. Specific intelligence is required, involving sharing data with ports of origin and following suspected shipments to the lab where the drugs will be extracted.

During my visits to ports and interviews with officials in the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Spain, Senegal, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Ecuador this year, I was struck by how unprepared they were. At Colombia’s ports in Santa Marta and Buenaventura, customs officials had little awareness of chemically concealed cocaine or methamphetamine.

In Dakar, Senegal, a room full of West African port executives was shocked when I stated liquid cocaine was one of the major threats facing the region.

How widespread is the problem?

The full scale of chemically concealed methamphetamine remains unclear, but the signs are troubling. The recent Spanish seizure points to Mexican-made meth spreading into Europe.

While the Los Angeles seizure has not been reported as having been cartel-made, the US Drug Enforcement Administration has reported that the vast majority of meth in the country comes from Mexican labs.

As for chemically concealed cocaine, it’s absolutely everywhere.

In June 2023, 1.6 tonnes of cocaine disguised as charcoal were seized in London.

In January 2024, 444 kilograms of liquid cocaine were found in Hong Kong labelled as white wine.

In August 2024, a Kenyan woman was caught on the way to Mumbai, India, with liquid cocaine hidden in shampoo bottles, further confirming a major cocaine trafficking route from East Africa to India.

In November 2024, customs officers at Washington Dulles airport found a package of cocaine masquerading as coffee grounds and powdered chocolate, having been smuggled in from Guatemala.

Drug traffickers are onto a winner here.