Are African Ports Ignoring Exposure to Organized Crime?

Cocaine from the west, heroin from the east, captagon and hashish from the north, and tramadol just about everywhere. African ports are expanding rapidly, but drug trafficking is keeping up.

Ports across Africa are on a shopping spree. Tema in Ghana, Maputo in Mozambique, Cape Town in South Africa, Tangier Med in Morocco, major seaports around the continent have recently completed or broken ground on expansions or signed deals to dramatically increase their cargo capacity.

But this breakneck pace is leaving behind severe vulnerabilities to organized crime and corruption that are not being attended to, several concerned industry observers told World of Crime.

Here, World of Crime breaks down the largest security challenges facing African ports and how organized crime is taking advantage.

New ports don’t fix old problems

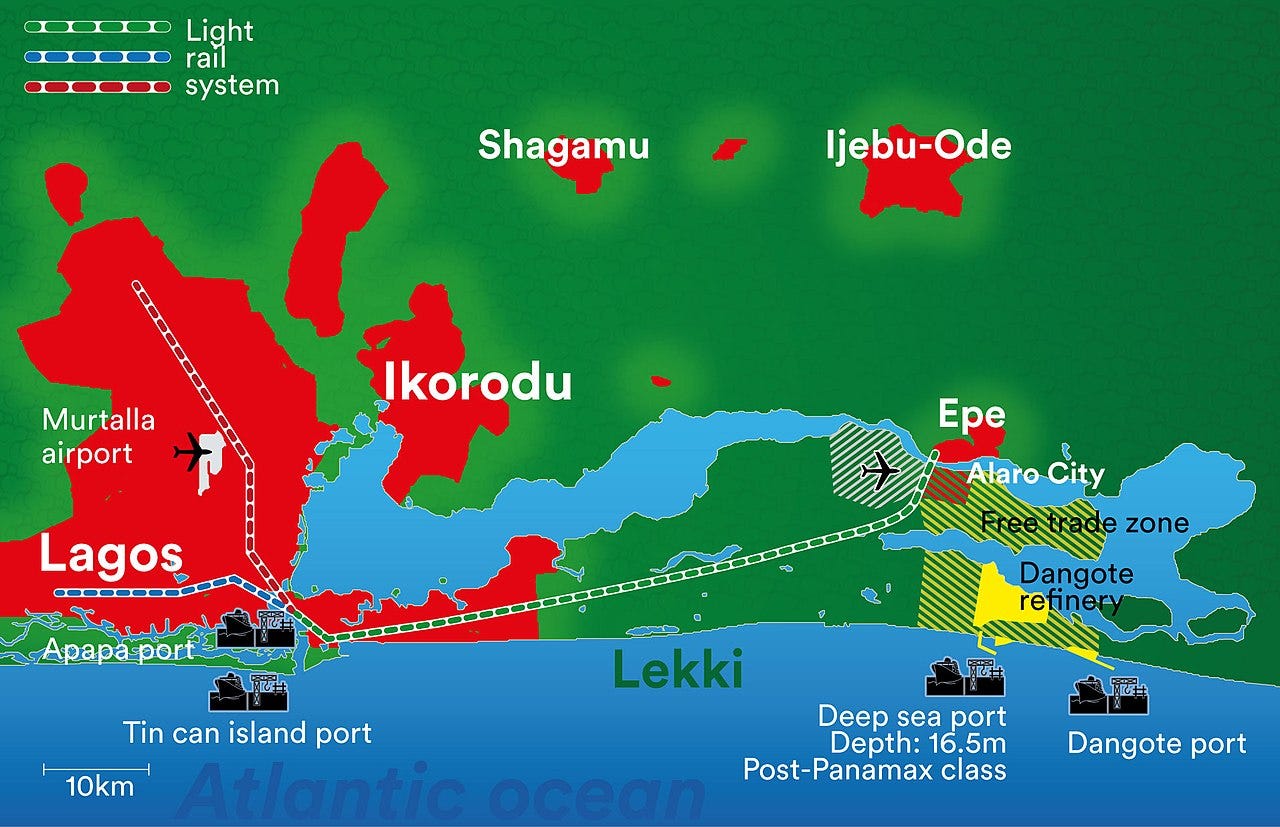

Nigeria is proud of its new Lekki Deep Sea Port, which opened just over a year ago. Shipping giants such as CMA CGM have proclaimed their part in helping the port break new ground and welcome an ever-wider range of vessels. A rapid infrastructure push in 2023 saw greatly improved road access, with 60 percent of cargo now leaving by road. A major railway line is being planned.

This is alleviating some investor concerns, given the history of transportation problems that have plagued the neighboring and congested Lagos Port Complex. Road access there has veered to the catastrophic, with the highway to the port so containers have fallen off trucks. Theft is commonplace. Goods go missing. Auto parts go missing.

Lekki is similarly helping to reduce congestion out at sea. Ships have to sometimes wait weeks to be able to enter the labyrinthine Lagos complex and unload their cargo. Shipping representatives described the situation at the Lagos ports as “total chaos” and “a disaster.”

But these improvements may only be surface-deep. The congestion in and out of the port of Lagos has been weaponized by corrupt government and customs officials. The level of ingenuity is almost impressive. Customs officials mounted several fake toll booths to extort any trucks entering or leaving the port of Lagos, according to a 2022 Deutsche Welle investigation.

An electronic call-up system created in 2021 to allow trucks to sign up to enter the port at specific times rapidly became another way for truck drivers to be extorted and forced to pay for preferential treatment. And to hide losses from corruption and theft, port authorities have regularly only released profit figures as a way to hide staggering losses, Deutsche Welle found.

Addressing road quality is one thing. Rooting out deeply entrenched networks is another.

“A lot of ports have varied capacity, they have different vulnerabilities. The challenges mostly start with infrastructure deficiencies and resources, such as poor funding by governments into security architecture,” said Ebunoluwa George Ojo-Ami, a maritime security expert focused on the Gulf of Guinea. “There can be a selfish interest behind this: corrupt personnel in certain agencies could be said to work with some organized crime groups. One of the biggest things for criminal networks is to infiltrate agencies with an insider.”

There is also little to no appetite for real collaboration and information-sharing. Ports are engaged in a race for more cargo and more investments, with commercial priorities far outstripping criminal considerations, said one expert.

“Port collaboration is also lip service. They do sit down together and discuss issues, but there’s huge competition for cargo from the Sahel region. These ports in West Africa are very close to each other. So if you put information out there, other ports will take advantage of it,” explained Dr. George VanDyck, a Ghanaian expert on port governance.

Without deep structural reform, as recommended by the Maritime Anti-Corruption Network, progress at Lekki and other ports will stop at the water’s edge.

Cocaine and heroin trafficking worse than ever

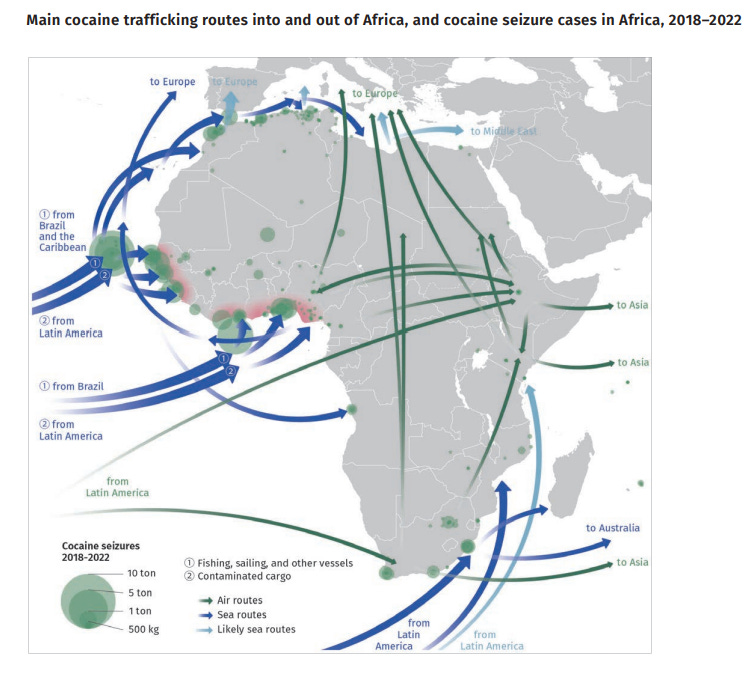

Lekki is just one example of a new port facing old struggles. New and expanding infrastructure at Kribi in Cameroon (opened in 2018), Walvis Bay in Namibia (expanded in 2019), as well as Mombasa in Kenya or Tema in Ghana (currently undergoing expansions) have not been able to stem the flow of cocaine from Latin America or heroin from South Asia.

African ports have become revolving doors for the international drug trade, with little being done to stop it. Old and new, modern and creaking, African ports are struggling to keep up.

Dr. Jonas Aryee, a maritime business researcher at the University of Plymouth, explained one such gap at the important seaport of Tema in Ghana. “Tema is divided into two. The port has containers either scanned by a local company [at older terminals], the other by MPS [an international joint-venture at the newer Terminal 3],” he explained.

For traffickers, the choice is obvious. There is far less chance of getting caught moving cocaine through the old terminals, he explained. And a tug-of-war for business between MPS and its local rivals has only worsened any chance for collaboration between operators at the same port, according to Aryee.

Geopolitical changes may only make the situation harder. In West Africa, cocaine seized in the Sahel region rose from 35 kilograms in 2021 to 863 kilograms in 2022, according to the UN’s World Drug Report 2023. And those numbers likely remain soft, given that 57 tons of cocaine were seized in or en route to West Africa between 2019 and 2022.

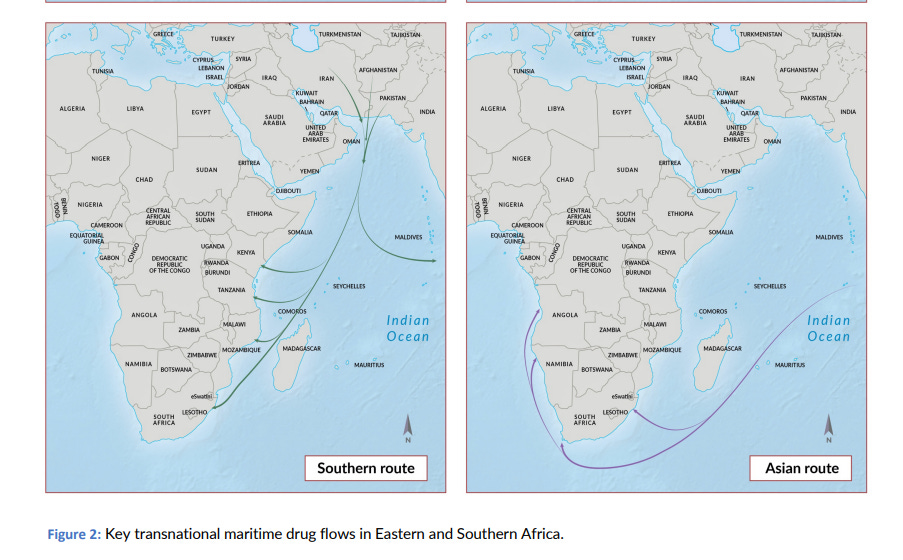

And while this has brought more law enforcement to West African ports, a portion of cocaine traffickers are targeting less watched facilities in eastern and southern Africa.

A December 2022 report by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC) identified the ports of Durban in South Africa, Pemba and Nacala in Mozambique, Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar in Tanzania, Mombasa in Kenya, and Walvis Bay in Namibia, as having seen more cocaine seizures.

Heroin and methamphetamine continue to pose severe health risks to African populations. The epicenter of global heroin production has shifted from Afghanistan to Myanmar, following a Taliban crackdown on opium poppy cultivation. But the port of Mombasa in Kenya remains the most important destination for heroin shipments being sent from south and Southeast Asia and then onto Europe, with the port of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, a close second.

Captagon and tramadol trafficking pose next generation of challenges

Growing cocaine and crack cocaine use in Africa, especially in communities nearest to ports and along trafficking routes, is a real cause of public concern. But most of the drug transits through Africa on its way to other markets.

The spread in popularity of captagon, a highly addictive stimulant, and tramadol, an opiate painkiller, within Africa has created a new challenge for ports and health authorities. These drugs are being trafficked to the continent to stay there. In November 2023, more than two million captagon pills were seized at Morocco’s port of Tanger Med, on their way to Lebanon to a destination in West Africa. This highly addictive stimulant, mostly manufactured in Syria, is seeing rapid growth in its use across northern Africa. Since the early 2010s, Sudan has been identified as a local hub for the production and distribution of captagon. But with a continuing civil war there, traffickers may seek other routes to supply their customer base on the continent.

But if captagon is still not widespread, the illicit use of tramadol is a full-blown epidemic. With half of all African countries reporting tramadol seizures, ports are besieged with tramadol seizures. In April 2023, 143.8 million tramadol pills, worth an estimated $138 million, were found at the port of Apapa in Nigeria. While West African ports in Togo, Benin, and Nigeria remain the main entry points for tramadol, its continued popularity may see seizures rise at a wider range of ports.

Competition between western and eastern ports may make things worse

West African and Eastern African ports present a vastly different criminal panorama, according to experts. While both regions are vulnerable to corruption and drug trafficking, West African ports do benefit from a history of increased security investment and the presence of a plethora of international firms.

“West Africa is more open, western powers have a vested interest,” said Aryee. “Eastern and Southern African ports have lost competitiveness in their port ranking because they are not ready to let in private sector investment. Mombasa in Kenya and South Africa do not allow foreign-based private players.”

Despite the entrenched corruption networks at many West African ports, Aryee pointed at the presence of international players like MSC, Maersk and Bolloré as having helped to bring in certain best practices.

While Kenya is now planning to partly privatize operations in Mombasa, there is a concern this lack of competitiveness has also put Eastern African ports on the back foot when it comes to dealing with criminal threats.

“The competition between West and East means that the East is far more exposed. This will be a major emerging criminal market for the next 20 years. The West has far better structures in place,” warned Vincent Gaudio, CEO of Amanar Advisor, a French business intelligence company working in Africa.

“The opening and expansion of new ports in East Africa is going to lead to new trafficking, be it drugs, weapons, or contraband clothing. Nobody is looking at the port of Bossasso for the Horn of Africa or Port Sudan along the Red Sea. Nobody is looking at the ships entering, including small ships trafficking weapons,” he concluded.

And the current conflict in Yemen and its expansion into attacks on maritime shipping in the Red Sea is only likely to ramp up the pressure on East African ports.