An Unpredictable Neighbor: Venezuela's election results

How will Venezuela's neighbours in the Caribbean, especially the Netherlands, respond to its post-electoral chaos?

Written by Sara Frisan, Arianna Lucà and Alessia Cappelletti of Dyami. Originally published here.

In this three-part series, World of Crime and Dyami, the Netherlands’ leading security intelligence company, have teamed up to delve into the political, international, and criminal challenges facing Venezuela, and why these developments matter for the Netherlands.

Understanding these dynamics is crucial for Dutch policymakers, businesses, and citizens in navigating the complexities of an interconnected world. In the first article of the series, we look at the Venezuelan elections held on July 28 and possible spill-overs.

Venezuela held its Presidential elections on July 28 and the situation is still evolving at the time of publication. For the first time in over a decade of growing autocracy, mismanagement, and economic crisis, hopes for political change are high – Venezuela could emerge from political and economic isolation and an eventual democratic transition. But challenging times lie ahead, whoever is confirmed the winner.

President Nicolás Maduro, who first came to power in 2013, has consolidated his power by securing control over the military and institutions like the National Electoral Council, the Supreme Court, and the judiciary through political repression, censorship, and rampant corruption. Under Maduro's rule, Venezuela, home to the largest world's oil reserves, suffered economic collapse, hyperinflation, and chronic shortages of essential goods.

Compounded by plummeting global oil prices and U.S. sanctions against the Venezuelan government and oil apparatus, the country tumbled rapidly into a tight economic recession that forced nearly 8 million people to leave the country. According to a UN Human Rights Council report, today over 80% of Venezuelans live in poverty and 53% are unable to afford food.

Recent polls had predicted a victory for the opposition, showing that most Venezuelans were eager for change and willing to exercise their right to vote. The favorite was opposition candidate Edmundo González Urrutia, the replacement for opposition leader Maria Corina Machado, who has been barred from running by the government. Despite efforts to disadvantage the opposition, most polls predicted Maduro and his United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) would lose by 20 to 40 points. However, in the early hours of Monday 29th July the National Electoral Council (CNE), controlled by Maduro allies, said Maduro had won with 51.2% of votes, against 44.2% for González Urrutia.

The result –and whether it is accepted– will be consequential for Venezuela, for its diaspora abroad, and the country’s foreign relations.

Contested results

On July 29th The National Electoral Council declared President Nicolas Maduro the winner of the presidential election, with Maduro claiming 51% of the vote against the opposition’s 44%. The result has been disputed by the opposition and many countries who observed the elections in the Americas and Europe. Leading opposition figure Maria Corina Machado claims González won 70% of the vote.

Opposition leaders claimed the election was rigged, saying that their witnesses were denied access to the CNE headquarters as the votes were counted, and that some votes were prevented from being processed. Instead, Maduro claimed elections were fair and that outsiders tried to interfere.

Large protests will lead to a crackdown by security forces supporting Maduro, who warned the opposition of a ‘fratricidal civil war’ if he lost the election. Maduro has expressed no intention to step aside, while more countries are joining the widespread international community's lack of trust in the results. The OAS will hold a meeting on Wednesday, 31st of July, to discuss the results.

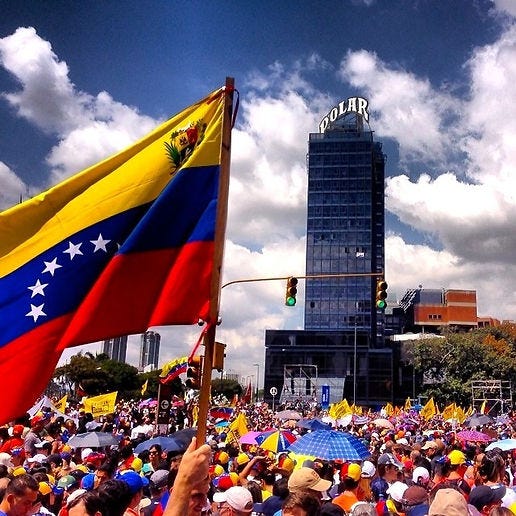

Despite the opposition leader calling for calm, protests took place in Caracas, and several other main cities, as well as other countries, including Argentina, against the election results on Monday evening.

Thousands of people took the streets of Caracas, chanting “Freedom, freedom” and “This government is going to fall”. Protesters around the country took down at least two statutes of Hugo Chavez, Maduro’s predecessor. Security forces fired tear gas and rubber bullets at protesters, some responded by throwing molotov cocktails and rocks.

Maduro’s government is not new to protests and demonstrations. In 2014, 2017 and 2019 protests against the government have become increasingly violent. Maduro’s government has been notoriously repressing dissent in the past, through violent crackdowns on street protests, jailing opponents, and prosecuting civilians in military courts, for the act of protesting, causing the human rights crisis that contributed to the Venezuelan exodus.

An important role is also played by the military and law enforcement authorities, as they enjoy a privileged position in Venezuela, which historically has a constructed militarized state apparatus. By giving the military money, prestige and power, Maduro has bought their political backing and their support, which Juan Guaidó, Maduro’s opponent in 2018, lacked. Currently, there are no signs that the military is breaking from the government.

Fraud and Electoral Manipulation

Venezuela has not held free and fair elections since 2013, and the opposition has been largely absent from elections since 2015 due to the government’s tested and proven repression and manipulation tactics.

In 2015, Leopoldo López, a prominent opposition leader, was sentenced to 14 years in prison, on charges of inciting violence during anti-government protests which the European Union defined as politically motivated. This followed a six-year ban from holding public office which began in 2008. In 2017, Henrique Capriles, another opposition figure, was barred from running for public office for 15 years, for alleged administrative irregularities. In 2023, the Maduro administration charged his most famous opponent, Juan Guaidó, with money laundering, treason, and usurping public functions, after years of intimidating him and his staff.

There are many more such examples. Most recently, the opposition's initial candidate, Maria Corina Machado, was banned from running in January 2024 over alleged fraud and tax violations, which caused the U.S. to reinstate sectoral sanctions lifted in October 2023. Machado has already faced criminal charges for her participation in anti-government protests 2014, when she also was stripped of her parliamentary seat.

Maduro, however, still has a challenger. González, a less well-known career diplomat of Machado’s party, was leading in the polls in the run up to the election. He has promised to revive the economy, restore independent institutions and free expression, and release political prisoners.

A free and fair election was far from guaranteed. Maduro has been manipulating both the campaign and the electoral process. Despite pledging to hold competitive elections, the regime holds power over key political institutions, including the National Assembly and the National Electoral Council (CNE). In mid-June 2024, six CNE members were forced to resign without explanation and the National Assembly immediately appointed a new CNE commission whose members have close ties to the ruling party.

Maduro has attempted to undermine the chances and credibility of the opposition through intimidation, deliberate arrests of opposition coalition members, journalists, and anti-government activists, and arbitrary disqualification of several opposition figures and electoral candidates, including Machado, from taking office. It is estimated that approximately fifty of the latest arrests among opposition ranks are linked to Machado and González.

In late June, the government banned ten sitting mayors from holding offices, after González and Machado held rallies in their cities. On July 18, 2024, the head of security for Machado was arrested by authorities on charges of gender violence. Both Machado and González condemned this as a deliberate provocation to weaken their security just before the election.

The government is also taking advantage of the state-owned media and social media to prevent coverage of opposition candidates and pushing the narratives of the ruling party.

Despite the Venezuelan Constitution guaranteeing the right to vote for citizens abroad, the government is imposing bureaucratic obstacles to prevent the Venezuelan diaspora from voting. Currently, only a few of the nearly 8 million Venezuelans living abroad have managed to register. The borders with Colombia were also closed on the 27th and 28th of July for ‘security reasons, preventing citizens living on the border from traveling back to vote.

The E.U. was not allowed to observe the elections, but the U.N. and the Carter Center provided limited election monitoring and kept their findings confidential. The Carter Center has mentioned they “will not conduct a comprehensive assessment of the voting counting, and tabulation process,” due to its limited presence.

Venezuela after the elections

These elections are crucial for stability in Latin America. Maduro’s alleged victory has lead to increased tensions throughout the region. Any rapprochement with the U.S. and lifting of sanctions will now be far harder and he will probably forge stronger economic ties with China, Russia and Cuba.

The alleged electoral defeat of the opposition and Maduro’s firm rejection of protesters' demands has closed the door to more cooperative relations with the international community. González was expected to pivot toward democratic governments in the region and with Washington, and work to rebuild international ties. He had announced plans to rebuild international ties with multilateral organizations, such as the IMF, the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank. With Maduro’s clinging to power, these options have been taken away.

The contested election is far from over, and more civil unrest and protests are expected to happen. Even minor institutional victories at lower levels of government, these elections show the hold of the PSUV over Venezuela’s political institutions. Dismantling those institutions built over years of PSUV rule will not be easy to clean up. Maduro’s party still controls the military establishment and is likely to crack down on opposition protests. Any transition to a new government would take place six months from now, giving plenty of time for Maduro to derail the democratic process.